Cold cases grow cold because their stories stop being told. Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office published an interactive map and timeline last year of over sixty missing and murdered people whose cases remain unsolved. We have taken on the task of writing about each and every one of those cases, to keep their stories alive and hopefully find justice for the victims and families. Remember, as Jean Racine, the French playwright once said, “there are no secrets that time does not reveal.”

Nearly six hundred miles south of the Southern Humboldt hamlet of Miranda, where the City of Angels meets the ocean, is Zuma Beach-the City of Malibu’s white sand crown jewel.

It was late December 1973– Malibu’s coldest month of the year—the Pacific was slate-gray.

23-year-old Miranda woman Theresa Terri Diane Walsh was taking stock of the Southern California winter. Back home, Walsh’s two-year-old son was in the care of his grandmother, Walsh’s mother, Goldie Smith. Walsh’s husband and she had separated, but their two-year-old boy tied them together.

We don’t know her reasons but for all the excitement Los Angeles offered, Walsh longed to return home. Perhaps, instead of the sea breeze, she wanted mountain air. Instead of palm trees, she wanted redwoods.

She contacted her mother and told her the good news: “I’m coming home for Christmas.”

Once set on returning home, Walsh tried to arrange a ride north, including using a group known as Hitchiker’s Anonymous to get north. But, no luck. This did not worry Walsh. That month alone, she had hitchhiked from the State of Washington to Los Angeles on her own. She had navigated the interstates with strangers and made it out on the other side.

In today’s age, these plans might have given someone pause. 1973 was a different era- the era of Easy Rider, two years before Janis Joplin sang of Bobby “thumbin’” a diesel down.

Walsh’s friends bid her farewell on December 22, 1973, around 9:00 a.m. They dropped her off at Zuma Beach. She wore bell bottoms, a lavender blouse, a faux-fur brown coat, brown hiking boots, and an olive green Boy Scout knapsack- the traveler-chic of a bygone era.

As the Pacific crashed into the continent, Walsh hitched a ride north and began her journey of 600 miles to spend Christmas with her mother and son amidst the mountains.

One can imagine Goldie Smith’s frenetic, loving energy of a mother preparing for her child to come home for the holidays. The anticipation, wondering what sort of woman her Theresa was coming to be. Would she look different? Act differently?

It was Christmas Eve, and Goldie Smith had not heard from her daughter Theresa. She’s resourceful. She’s tough. She’ll walk through the door at any moment.

Christmas Day came and went with no sign of Theresa. What was supposed to be a day of homecoming was likely a day of nerves and distress.

Each day after Christmas, Goldie Smith’s thoughts of “she’ll be home any minute” probably were drowned by a downpour of nerve-racking what-ifs.

Finally, Smith gave in. She contacted the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office on December 31, the last day of 1973, and reported her daughter Theresa as a missing person.

Mark West Creek is a 52-mile-long watershed in Sonoma County that flows east to west. Its headwaters lie northeast of Santa Rosa flowing westward. Its waters would converge with other tributaries and eventually meet with the Russian River, flowing through the rolling hills of Sonoma County to Jenner merging with the Pacific.

On December 28, three days after Christmas, Mark West Creek was swollen with recent rains. Two youths were on their own adventure traveling the waterway in their kayaks.

That day, fun would abruptly transform to fear. In the cold, fast waters of Mark West Creek, the pair spotted a woman’s body in the water, partially submerged, the current pressing her against a log that had collapsed into the waterway.

The Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office would respond. The woman was young, her hair was dark, and her body was nude. She had been in the water for approximately one week. Her hands and legs were bound with a generic nylon cord contorting her body into a crouching position. There was a rope around her neck.

250 miles north, the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office would take note of a report filed by their colleagues to the south. A brown-haired, young woman was found naked, bound, and strangled in a creek. Maybe it’s Theresa?

A Sonoma County deputy would retrieve the fingerprints of the dead woman and compare them with prints in the Department of Motor Vehicle’s Records. They were a match.

On January 9, the media would announce investigators identified the woman found dead in Mark West Creek as Theresa Walsh, the 23-year-old Miranda woman who had left Los Angeles just days before to see her mother, son, and home for Christmas.

With her formal identification, fragments of Theresa Walsh’s story came to light. She had a two-year-old son. She was separated from her husband. She hitchhiked “all over.”

Sonoma County Sheriff Don Stripeke expressed his disapproval of hitchhiking to the Petaluma Argus-Courier saying, “It’s unbelievable to me but you see it everywhere. It seems no matter how many times law enforcement officials report the results of hitchhiking, or school officials talk about it, they still persist.”

Up north, in the shadows of the forest, as the fog moved over the hills, Goldie Smith was left with a child who would never know its mother, the blank space of a dead daughter, the Christmas homecoming that never was.

Instead of returning home, 23-year-old Miranda woman Theresa Terri Diane Walsh was killed by an unknown suspect. Instead of getting to hold her son again, Walsh would become one of six women who fell into the web of a predator stalking and preying upon the young women of Sonoma County.

Instead of returning to the redwoods, Walsh would become one of many. Her death and five others would be etched into the history of West Coast Cold Cases.

Law enforcement, criminologists, and armchair investigators alike seem to agree that from 1972-1974, a killer was on the hunt in Sonoma County, stalking young women hitchhiking along a stretch of Highway 101.

The Santa Rosa Hitchhiker Murders have been examined countless times by journalists, documentarians, podcasters, true crime aficionados, and amateur sleuths alike. We combed Sonoma County newspapers in that era 1972-1974 Santa Rosa’s Press Democrat and the Cloverdale Reveille, and the Petaluma Argus-Courier.

In the spirit of our coverage of cold cases, we set out to bring life to Theresa Walsh, a native daughter of Southern Humboldt. Sadly, who she was got lost in the deluge of violence. As daughters were found dead and fear took hold, these individual women became a bullet point. We want to tell their story.

They Were Ice Skating, and Then They Were Gone

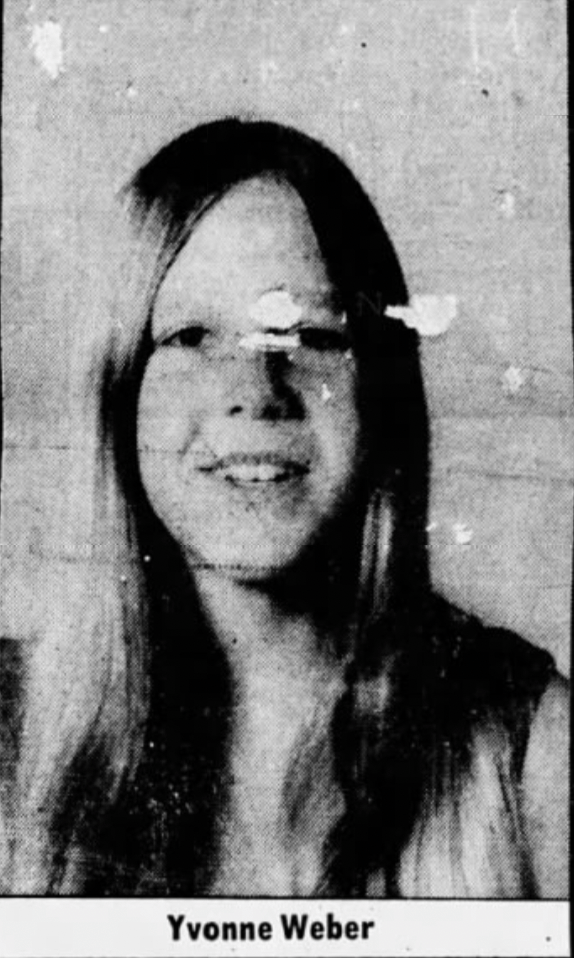

On the night of February 4, 1972, 12-year-old Maureen Sterling and 13-year-old Yvonne Lisa Weber were two teenage girls living in Santa Road living their middle schooler lives. The pair skated at the Redwood Empire Ice Arena and left around 9:00 p.m. set on hitching home. They would be seen that evening northwest of Santa Rosa, on Guerneville Road, and then vanish.

Eleven months later, on December 28, 1972, skeletal remains would be found down a steep embankment along Franz Valley Road, approximately thirty miles northeast of where the girls had been last seen hitchhiking

Decomposition left the remains unidentifiable. There was no clothing in the area. Maureen Sterling’s mother would eventually identify the remains after recognizing an earring, a set of orange beads, and a 14-carat gold cross her little girl wore that were found at the scene. The young woman’s matching earring would never be located.

A College Girl Trying to Get Home From Work

It was March 4, 1972, one month after Sterling and Weber would disappear while coming home from the ice rink. 19-year-old Kim Wendy Allen got to the end of her shift at Larkspur Natural Food and needed a ride north to Santa Rosa, where she was an art major at the local junior college.

She hopped a ride with two men who dropped her off in San Rafael. This left nearly forty miles remaining till Santa Rosa. The two men watched as she hopped out of their vehicle near the Bell Avenue Exit of Highway 101 and the spunky young woman wearing an aluminum-framed, orange backpack put her thumb back in the air to continue north.

She would not come home that night. Instead, Allen would be found the next day dead, discarded, and undressed down an embankment along rural Enterprise Road, a roadway that runs towards Bennet Valley southeast of Santa Rosa.

Investigators found that an unknown assailant had tied the young woman up using a cord, binding her hands and ankles. Evidence indicated she was raped and then her killer took their time and strangled her for over thirty minutes till she died. Semen was found on her body. There was an oily substance on her that investigators thought was similar to oils used in machine shops. Detectives would locate a single gold loop earring at the scene. The matching earring would never be recovered

About two weeks into the investigation, Sonoma County Sheriff Donald Striepeke would call in a University of California, Berkeley criminologist by the name of Peter D. Barnett hoping the academic assistance could assist in cracking the case.

The March 29, 1973 edition of the Press Democrat announced law enforcement had arrested a 38-year-old auto mechanic by the name of Robert Lee Bushon for kidnapping and assaulting a 22-year-old woman.

Police reported Bushon allegedly picked up a hitchhiker near Sebastopol, tied her wrists, and then drove to his Santa Rosa apartment where he forced her to undress. The woman would escape the following morning. The sheriff’s office announced they would be looking into Bushon and his possible connections to the death of Kim Allen.

Twenty days after 19-year-old Kim Allen was seen alive, an unknown person deposited her checkbook in a mailbox near the Kentfield Post office, 43 miles from where her body was located.

A Runaway Doesn’t Come Home

Seven months after Kim Allen was killed, 13-year-old middle schooler Lori Lee Kursa was reported missing by her mother on November 11, 1972. Kursa had slipped away from her mother while the two shopped at a grocery store that day.

The young lady had a chaotic home life and frequently hitchhiked while running away from home. There are reports she was seen with friends on November 20 or 21. A witness reported seeing Kursa hitchhiking on November 20.

On December 14, 1972, Kursa’s dead body would be found naked lying fifty feet down a ravine that ran alongside Calistoga Road, an isolated roadway northeast of Rincon valley.

Investigators determined Kursa had died of a broken neck causing compressing and hemorrhaging of the spinal cord. There was no evidence she had been raped and no cords or garrotes located where she was found.

Multiple witnesses came forward: one said they had seen Kursa with two men on Calistoga Road; another said they saw her with a bushy-haired Caucasian man sitting in a truck parked where she was later found dead.

One witness described seeing Kursa with two men between December 3 and December 9. The teenage girl appeared impaired and two men carried her between them reportedly pushing her into a van. One was described as a white man with bushy, Afro-like hair.

Based on witness testimony and analysis of Kursa’s body, investigators would postulate that the 13-year-old was kidnapped and pushed into the back of a van where she was stripped of her clothing. In an attempt to escape, Kursa would exit the moving vehicle, breaking her neck and falling down the ravine where she lay until she died.

As the number of victims increased, and the public outcry for justice intensified, the Press Democrat and other local media would start to play a direct role in helping to solve the cases.

On December 27, 1972, the newspaper’s managing editor Art Volkerts announced the newspaper would be raising funding to pay for rewards to entice “secret witnesses to come forward. The newspaper generated a letter correspondence system that would allow anyone with information to maintain their anonymity. If the information offered by a “secret witness” resulted in an arrest and conviction, these witnesses could identify themselves to the Press Democrat and be rewarded.

A Shasta County Runaway Last Seen By Grandma in Garberville

A month and a half after Lori Lee Kursa was found with a broken neck off of Calistoga Road, 15-year-old Carolyn Nadine Davis had enough of her Shasta County home outside the town of Anderson and ran away. Shortly after leaving home on February 6, 1973, Davis would send a letter to her parents saying that she never planned to come back home.

By July of that year, Davis found her way to Garberville where her grandmother lived. Davis stayed for two weeks and then got the itch to travel once again telling her grandmother she intended to hitchhike to Modesto.

On July 15, Davis’s grandma drove her to Garberville’s downtown and the young woman would be seen trying to hitch a ride on Highway 101 southbound later that day.

Sixteen days later, Davis’s body would be found stripped of her clothing three feet from the same location that12-year-old Maureen Sterling and 13-year-old Yvonne Lisa Weber had been found dead seven months earlier.

Investigators would determine Davis most likely died on July 20, five days after her grandmother said goodbye. Her cause of death was determined to be strychnine poisoning. Medical examiners found wounds on her right ear consistent with someone trying to pierce her earlobe.

The Last, But not the Least

The winter of 1973 would bring the death of 23-year-old Miranda woman Theresa Walsh, the last victim sleuths confidently attribute to the Santa Rosa Hitchhiker Killer. Her killing occured five months after Caroline Davis.

Walsh’s remains were found within 100 yards of where Lori Lee Kursa’s remains had been found a year earlier. Mark West Creek parallels a section of Calistoga Road.

On January 10, 1974, the Press Democrat reported that the FBI stepped into the Theresa Walsh investigation, analyzing the nylon rope that bound her hands and feet. Investigators hoped the analysis could point towards a rope manufacturer and then distributor that could lead to the identification of suspects. This did not pan out. The FBI found the rope too common to be traceable

Other Possible Victims of the Santa Rosa Hitchhiker Killer

More and more women have been identified as victims of the same person that killed the previous six women. These other women were connected due to their commonalities with the previous six, like the fact they were hitchhiking when they were last seen, being found tied up by nylon cord, or being dumped in similar locations

On April 25, 1972, 20-year-old Santa Rosa Junior College student Jeannette Kamahele hitched a ride down Highway 101 from the Cotati on-ramp. A friend of Kamahele’s would tell investigators she got into a brown Chevrolet pickup truck with a makeshift camper driven by a Caucasian male with an Afro-hair style. She was never seen again.

Seven years after Lori Lee Kursa was found dead of a broken neck off the side of Calistoga Road, The unidentified remains of a young, white woman were found 100 yards from where Kursa’s body was found. Thought by some to have been killed between 1972-1974, the unidentified woman was hogtied, her arms were fractured, and she was stuffed into a duffel bag.

15-year-old Kerry Ann Graham and 14-year-old Francine Marie Trimble, two teenage girls from Forestville, disappeared in mid-December of 1978. The pair’s final movements are foggy, but a friend reported the last time they had seen Graham and Trimble they were planning to hitchhike to Santa Rosa to attend a party. Later, unsure exactly when, a friend witnessed them hitching a ride at the Forestville gas station.

Trimble told her mother they were going to Santa Rosa’s Coddingtown Mall to Christmas Shop leaving sometime on December 15. After not returning home for a few days, the girls were reported missing. In July 1979, two dead bodies in an advanced state of decomposition would be found 12 miles east of Willits along Highway 20. An earring shaped like a bird was found where the bodies were dumped.

In November 2015, those remains would be identified as Kerry Graham and Francine Trimble. Trimble’s sister would identify the bird-shaped earring as an item she had given Francie, but its match was never located.

Connections or Coincidences?

To keep the scope of the analysis workable, when exploring patterns and commonalities in these cases, we will refer to the canonized six victims of the Santa Rosa Hitchhiker Murderer (Maureen Sterling, Yvonne Weber, Kim Allen, Lori Lee Kursa, Carolyn Davis, Theresa Walsh). Of course, there is a diversity of perspectives on murdered women that should be included in this list.

All six victims were found dead along rural roadways within a short drive of Santa Rosa, the county seat of Sonoma County.

All six victims were found naked.

The youngest victim was 12 and the oldest was 23. In the scheme of life, all of the women were young.

Lori Kursa and Theresa Walsh’s bodies were found near each other. Kursa’s was on the embankment below Calistoga Road whereas Walsh’s body was further down making it to the waters of Mark West Creek.

All six women were hitchhiking, an act of radical trust and some would argue youthful naivete once common for youngsters to engage in.

On April 10, 1974, the Press Democrat published an editorial that called for more punitive measures levied at convicted rapists arguing the trauma of sexual violence is exacerbated when “the rape victim is frequently put on trial instead of the accused victim.” The editorial argues that “rape has increased with the increase of hitchhiking by young women. It has led to bodily harm, and in at least five cases, in Sonoma County, murder.

Three of the six victims were found with or nearby an earring that was known to be theirs, but the matching earring was missing. Analysis showed that an unknown individual attempted to pierce Carolyn Davis’s ear before she was killed with strychnine.

One point of comparison of the six deaths that’s worth noting: the murder weapon. Maureen Sterling and Yvonne Weber were too decomposed to determine how they died. Lori Kursa appeared to have died as a result of an accidental neck break as she escaped whoever was kidnapping her. These three women cannot be used when comparing. This leaves Kim Allen and Theresa Walsh bound by a cord. Compare that to Nadine Davis, who was poisoned with strychnine. These murder weapons are drastically different. Serial killers sometimes change their modus operandi. More often, they do not.

Lastly, an important geographic parallel. Between 1972-1974, six Sonoma County women met the same grisly fate dying violent deaths at the hands of an unknown killer.

As we have explored in our reporting, between 1975-1976, four women hitchhiking in Humboldt County would also die at the hands of an unknown killer. Their bodies would be found mutilated and discarded on the side of Humboldt’s rural roadways.

In many ways, these two sets of killings share some essential components. Young hitchhiking women were targeted. The killers used a rural backdrop to cover up their crimes.

Connection or coincidence?

Suspects

The Santa Rosa Hitchhiker murders have proven a fertile ground for speculation as to possible suspects.

Some of the bigger name suspects include The Zodiac Killer, Arthur Leigh Allen (a man suspected of being the Zodiac Killer), Ted Bundy, Kenneth Bianchi and Angelo Buono Jr. (the pair known as the Hillside Strangers of Los Angeles).

All of these speculated suspects have circumstantial evidence reasons to point towards them, but nothing convincing enough for law enforcement to press charges.

41-year-old Santa Rosa man Frederic Manalli taught creative writing at Santa Rosa Junior College. He died in August 1976 in a head-on collision. In his belongings, “sadomasochistic drawings” were reportedly found depicting a former student, Kim Wendy Allen, the third canonized victim of the Santa Rosa Hitchhiker Murders. This fact has led some to believe Manalli is a possible suspect.

Jack Bokin is another speculated suspect. In December 2020, Bokin died in prison at the age of 78, just months before DNA confirmed he had murdered Michelle Marie Vael in 1996 leaving her body on Stony Point Road, a rural roadway south of Santa Rosa.

As is all too common in media coverage of heinous crimes, as the body count rose and more women fell victim to the Sonoma County Hitchhiker Murderer, their individual stories became less central to the coverage. The brutality of these crimes took on a momentum of its own. These women were stripped of their humanity by the very inhumanity that ended their lives.

This project is dedicated to breathing life into Humboldt County’s missing and murdered. Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office Cold Case index lists over 75 souls who have either died at the hands of an unknown suspect or disappeared nowhere to be found. Every one of them lived a life worthy of our empathy.

So, consider 23-year-old Theresa Walsh. Christmas was in three days. The Pacific Ocean lay slate-gray in the Los Angeles winter. For the last month, she had grown confident, thumbing her way from Washington State to the City of Angels.

But, she longed for home, her two-year-old son. She thought of her mother holding him, caring for him while she thumbed up and down the West Coast. Maybe Theresa thought about her husband, the father of her boy, and the circuitous paths of love and frustration.

We know Theresa Walsh drove with someone north out of the Los Angeles Basin. From there she could have taken Highway 1 along the California Coast. She could have stopped in Santa Barbara, Carmel, or Monterey. She could have put her feet in the sand. Likely, Walsh made her way into the San Francisco Bay area.

Or, Walsh could have taken the inland route, driving the never-ending flat of the Central Valley, passing by sleepy farming towns, watching the nation’s breadbasket pass by. From there, she likely would have also ended up in the San Francisco Bay Area, cutting inland via Interstate 580.

As any resident of the Emerald Triangle knows, the land and air and sky do not start feeling like home until, at the very earliest, when driving by Frog Woman Rock between Cloverdale and Hopland. Something about the gravity of the rock face and the Russian River acts as a portal to the land of California’s rural north. Others describe Willits as the true gateway to the Emerald Triangle, where the greens are greener, the trees are taller, and the air is cooler.

Next time you are making that long drive back home, think about Theresa Walsh. As you breathe in that clean air, as you look across our vast vistas, as you put your feet in our rivers, think about Theresa, and how lucky we are to be home. She died in pursuit of the simple yet vital sense of security and comfort we all seek: to head on home.

Sobering, and a well written public service heretofore unseen in Mendocino County journalism,

Thanks for that, Michael. It’d been a while since a cold case article. I’m glad I dove back in.

This was such a well written article. I have been interested in these cases for so long having lived in Sonoma County since 1980. My husband grew up in Eureka (My married name is Hegy, there is a portion of the hwy in memory of his grandfather and a plaque at the rest stop up by Westhaven.) I wish this/these case(s) could reach a bigger population of people. Does anyone know if there has ever been a movie or a limited series? I am a screenwriter, who would be the ultimate go to for information about this case?